How Black Friday became an international holiday

Find out where Black Friday came from and where it's going in the next 10 years in our interview with the Retail Doctor, Bob Phibbs.

It’s the biggest shopping day of the year, a global phenomenon, and you can’t miss it.

That’s right. Black Friday is back again.

Whether you’re a consumer sat behind a computer screen, venturing into a physical store or a company offering discounts on coveted items, it’s big business.

In 2020, the most popular item on Black Friday in terms of internet searches was the Nintendo Switch, which was looked up 2.98m times.

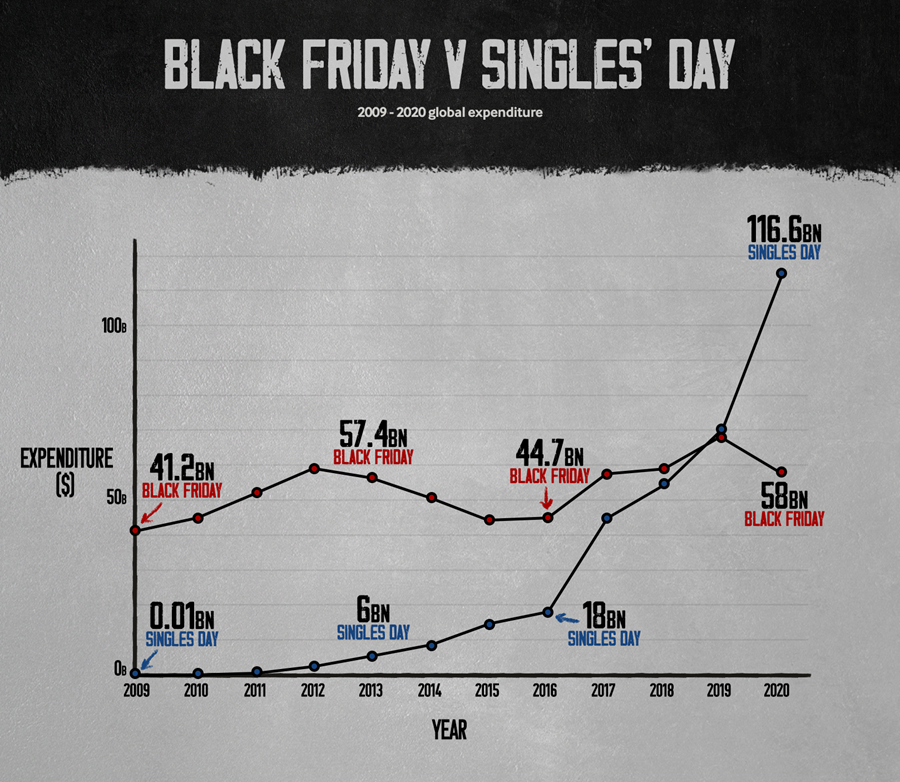

The global expenditure, meanwhile, was $58bn. To put that figure into context, that amount of money would put someone 21st on the 2021 Forbes Rich List.

Given its potential to pull in such large numbers of customers, it makes sense that Black Friday is pushed aggressively by large businesses, but how did this marketing juggernaut begin?

Traditionally, the day after Thanksgiving would mark the start of the Christmas shopping season in the USA – no stores would advertise the festive season until then.

The term Black Friday itself first appeared in 1960s Philadelphia, as retail expert Bob Phibbs explains, and was used to refer to the busiest shopping and traffic day in the city.

“The streets and department stores of downtown Philadelphia were mobbed,” says Phibbs, speaking to Betway online casino.

“By the ‘80s, it was an urban legend that it was the day retailers moved from reading losses to black ink profits,” he says.

“The entire period from Black Friday through to December can actually be a time that erases all losses from the previous three quarters and makes a business profitable for the year end.”

It pays to be involved, then.

But while it is undoubtedly a profitable promotion for retailers to take part in, it does seem paradoxical that offering such a range of discounts – in turn bringing their margins lower – can bring in the big bucks.

The answer to that, according to Phibbs, lies in the innovation of big businesses and the extension of Black Friday into a multi-day event.

“It’s the biggest of the big,” he says.

“The Walmarts and even Amazons launched their Black Friday deals back in October. We can also look at Prime Day in the summer.

“There used to be Cyber Monday that was a big deal before we had apps and people had internet in their homes.

“People came back to work and did their shopping on Monday because that was the only time they could actually get online. That’s not the case anymore.

“People have more time to do their shopping.”

It is true that the advent of technology that puts everyone online 24/7 has meant Cyber Monday as an independent event has been swallowed under the umbrella of Black Friday.

It does still exist in name, though, and is the bookend to the traditional weekend of discounts. In 2020, a total of $10.84bn was spent across the globe on Cyber Monday alone.

But with huge corporations controlling much of the Black Friday narrative, the outlook has the potential to be unforgiving for independent retailers.

“Most smaller retailers really would do well to not even try to compete on the day after Thanksgiving,” says Phibbs, who also goes by the alias of the Retail Doctor.

“That’s why Shop Small, which was originally started by American Express and Small Business Saturday, began.”

Small Business Saturday takes place on the Saturday after Thanksgiving, and first took place in 2010.

It was created as a counterpart to Black Friday and Cyber Monday to, as the name suggests, drive up sales for smaller, local businesses by using the former’s popularity as a boost.

“Something like 85 to 90 per cent of businesses still have transactions in a physical brick-and-mortar space,” says Phibbs.

“It’s about putting a focus squarely on the high street and putting out a big welcome sign for customers. It’s all about community.”

The runaway global success of Black Friday has also led to copycat sales across the world.

Singles’ Day takes place every year in China on 11 November and was originally a holiday to celebrate people who are not in relationships, ostensibly the opposite of Valentine’s Day.

Every year since 2009, online retailer Alibaba has turned the day into a 24-hour festival of shopping, offering huge discounts. In 2020 alone, $116.6bn was spent – easily eclipsing Black Friday.

Singles’ Day isn’t the only retail holiday to follow in Black Friday’s footsteps, Mexico’s El Buen Fin and Australia’s Click Frenzy are just two more where upwards of $100m are taken.

“If you have enough of a customer base who know you, you can do these kind of things,” says Phibbs.

With retail holidays such as these cropping up all over the world, and popularity for them growing exponentially, it’s impossible to also stop the original from changing with the times.

“I think Black Friday, as I grew up with it, is dead,” says Phibbs.

“The idea that there’s this door buster and there’s a $10 TV, there are only eight of them and you better be one of the ones to line up for eight hours to get it, I think those days are gone. That’ll never happen.

“We don’t really want those days to come back because it’s almost impossible to manage.

“But I think we’re going to continue to see more niche events that can get people excited. We’re certainly seeing more innovation coming out of Asia, and other places as well – look at Singles’ Day.

“Chinese New Year used to be a niche thing, now it’s everywhere. It gives you a chance to go out to a different consumer and it gives you a chance to give people the feeling that they matter.”

In a constantly changing retail environment, what can we expect from Black Friday in the next 10 years?

“I think the name will still be around, no doubt because people will have been used to it,” says Phibbs.

“But I think if you were to ask the younger generation in 10 years, they’re probably not going to care so much. It doesn’t have that pull.

“It’s more the mental check mark that’s the official start of the holiday season.

“Thanksgiving is wrapped up in American history and that’s kind of problematic, but everybody can understand Black Friday.”