Inside the launch of the Hubble Space Telescope

Meet one of the crew members responsible for launching the most important telescope of a generation.

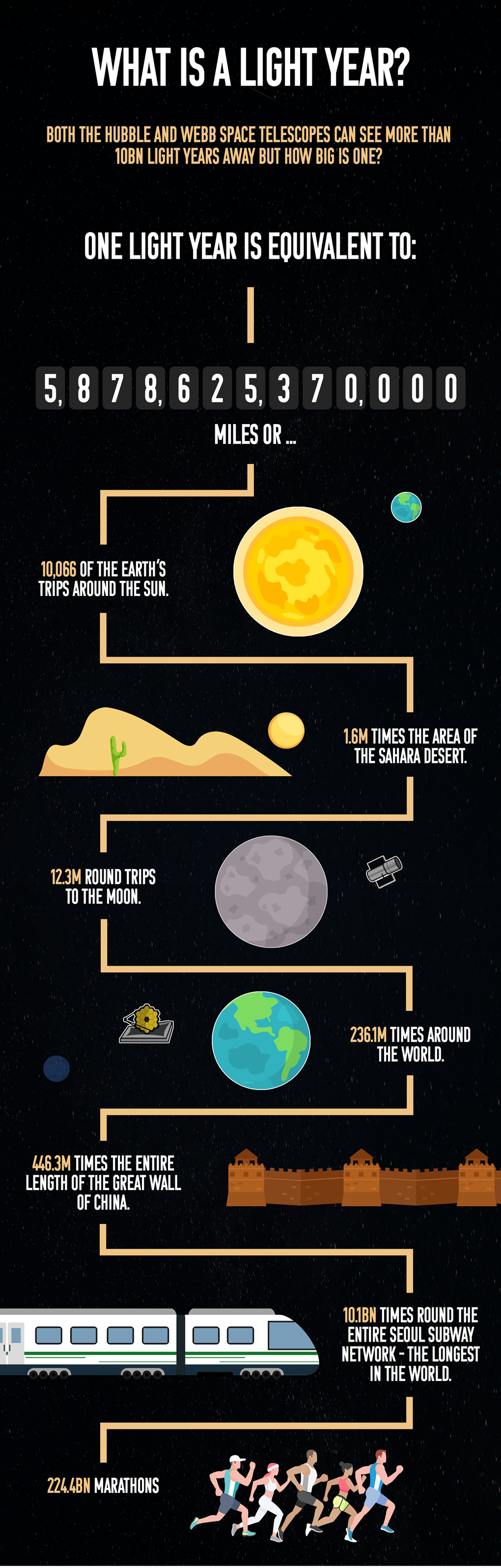

Space is big. That’s the ‘at least the 23 trillion light years in diameter’ version of big, not the ‘look at the size of this fish I caught’ version.

For context, just one light year is equal to 5.8 trillion miles.

But the truth is the universe is, in fact, so large that we currently have no way of telling its exact size.

So massive are the measurements we use when talking about distances in space, the number of zeroes would make anyone writing them with a character limit feel nervous.

To get an idea of scale, it’s probable that light would not be able to travel from one end of the universe to the other before the universe ends.

Light travels at 186,000 miles per second and the end of the universe isn’t predicted to be for at least 200bn years from now, so don’t start planning for Doomsday just yet.

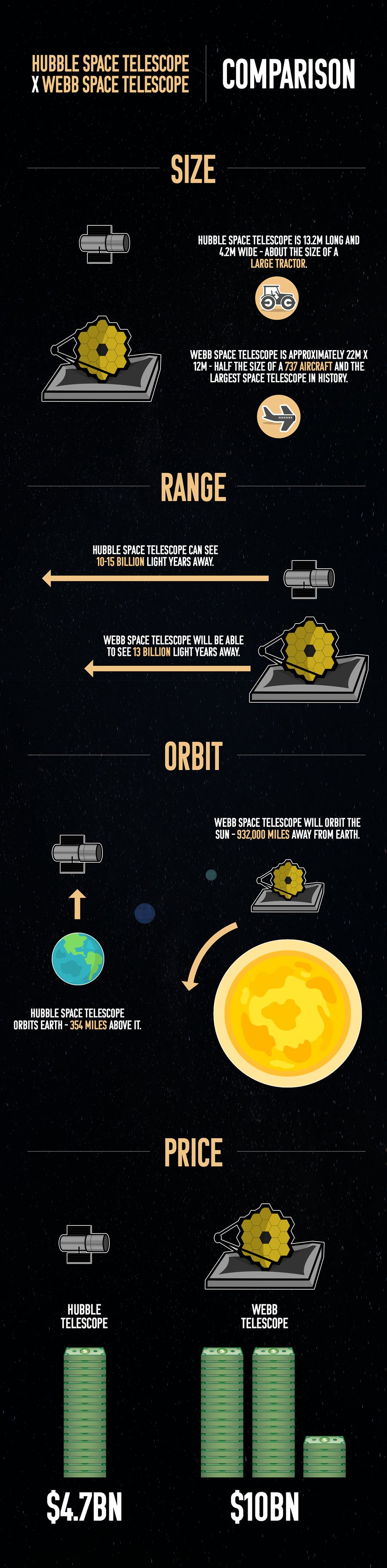

The most important piece of technology that has helped us establish the limits of the observable universe - 94bn light years, in case you were wondering - is the Hubble Space Telescope, which is basically an observatory in the sky.

Hubble was the first major optical telescope to be placed in space and, above the distortion of the clouds and earth’s atmosphere, it has given us a more detailed view of the universe than ever before.

But after 31 years of service, the Hubble Space Telescope is soon to be replaced by the Webb Space Telescope.

Dr. Steven Hawley was one of the crew responsible for placing the telescope into orbit in 1990, a role that brought with it major responsibility.

“For some 30 years, Hubble has been in orbit,” says Dr. Steven Hawley, speaking to Betway online casino.

“It has been revolutionary for astronomy. Far more so than at least I had imagined it could be. It was critically important.”

Now a director of engineering physics and a professor of astronomy and physics at Kansas University, Dr. Hawley knows what he is talking about.

The 69-year-old spent 770 hours and 27 minutes – more than 32 days – in space across five separate Space Shuttle missions between 1984 and 1999.

Most notable of those were the Hubble launch mission in 1990 and the Hubble maintenance mission in 1997, officially known as the STS-31 Discovery and STS-86 Discovery.

But for Dr. Hawley, his personal journey to outer space was one that he initially thought would never get off the ground.

“I followed the space program as a kid,” he says. “Al Shephard launched when I was in fifth grade.

“But I never thought I could be an astronaut because they were all military test pilots and I wanted to be an astronomer.

“It wasn’t obvious to me that I had the necessary skill set to be successful. I had never flown an aeroplane before or done anything particularly dangerous.”

After seeing a job advert from NASA on the bulletin board at the University of California while studying for his Doctorate in 1977, though, he took his first steps towards the stars.

Not that it was a straightforward path to launching the telescope that would make history.

“It was all about being in the right place at the right time,” he says.

“The truth is when I was selected for NASA, it wasn’t obvious I was going to space.

“We were all hired into a position called ‘astronaut candidate’. You would go through training and evaluation for two years and if you were successful, they would remove ‘candidate’ from your title.”

Dr. Hawley was eventually assigned to his first mission in February 1983 – nearly five years after joining NASA – but it wasn’t for another seven that he took part in the Hubble launch.

“The preparation involves a lot of different aspects,” he says.

“There's sort of classroom work you do, there are simulators, there's a physical training course and, in my case, I had to learn to fly the jets to begin with because I had never flown anything before.”

The move from classroom to cockpit was, as Dr. Hawley explains, an exciting one.

“The way the cockpit works, for launch and entry at least, is you have a three-person team made up of the commander, the pilot and the flight engineer,” he says.

“I was always the flight engineer. I enjoyed that opportunity. The flight engineer sits behind and between the commander and the pilot.

“My job was to help them through the ascent and entry procedures, not just the normal procedures, but in the event we had a problem. That gave me the opportunity to learn a lot about how the shuttle works, which I enjoyed.

“For the two Hubble missions, in addition to being a flight engineer for launch and entry, I was the prime robot arm operator.

“I had to lift the Hubble telescope out of the payload bay and release it. It sounds easy, but it was actually fairly challenging.

“There’s no collision avoidance software, so you have to be the collision avoidance person. You don't want to drive the telescope into the orbiter.

“We have displays that give us information about position and orientation, but primarily I was looking out of the window.”

But what about the question we all want to know the answer to: what’s it like to deal with zero-gravity in space?

“I never found it to be the kind of euphoric experience that people probably imagine,” Dr. Hawley says.

“I suppose in part, it's because it affects your efficiency and we always had lots of work to do.

“You're dealing with the fact that you’ve got to think about where your feet are. If they're not anchored, then you're going to float away or you're going to lose your pencil.

“When you're weightless, that also leads to certain physiological reactions including nausea.

“If you're upside down in the spacecraft, your eyes are telling you that you're upside down but your inner-ear doesn't sense it.

“I was fortunate that I never had that symptom, but I had a backache and a headache.

“The way we would plan for it in-flight was by timing how long it took to do something on the ground and then adding 50 per cent to account for weightlessness.”

Factor in the distraction of working while having a view of the earth’s landscape from above and it’s easy to appreciate how difficult it would be to stay focused.

Yet Dr. Hawley was initially most impressed with the realism of the software NASA used for his training.

“After my first launch, my first thought wasn't, ‘Wow, look at the earth,’ it was, ‘Wow, that simulation is really good,’” he says.

“But one of the things I do remember is that the earth was really cloudy all the time, and that kind of surprised me.

“You spend most your time flying over water, so you looked out of the window, odds are you're going to be over an ocean somewhere.

“The other thing I remember is the different landmasses do look distinct based on colouring and terrain and I got to the point where I could basically tell where I was over the earth.

“Australia is very red, South America and the Andes are kind of chocolate brown and you can obviously see deserts in Africa.”

That, along with having played a part in such a significant scientific event, isn’t something you forget in a hurry.

Even now, the importance of the legacy of Hubble, and his involvement in it, is not lost on Dr. Hawley.

“Every year on the anniversary of the launch of the telescope, I send a note to my crewmates and maybe share with them a few of the recent Hubble discoveries,” he says.

“I tell them that we get to say we had a very small part in making this discovery happen.

“It’s something we think about all the time, even 31 years later.”