Simon Taufel on the secret lives of umpires

The five-time ICC Umpire of the Year tells us about the side of officiating you don't see, and discusses what cricket can learn from a difficult year.

"The best way I can describe it is that umpiring chose me. I didn't choose it."

Simon Taufel is sitting in a hotel room somewhere near Newcastle, Australia, reminiscing about his career over Skype.

Having spent more than a decade as an ICC umpire – taking charge of 74 Tests, 174 ODIs and 34 T20 internationals – Taufel is no stranger to life on the road.

But, now semi-retired, this trip is for pleasure, to watch his daughter compete in an Under-12s regional tournament.

“When I pulled the pin on my international career," he says, "I sort of thought that I'd lost a lot of my two boys growing up, and I didn't want to lose my daughter."

Taufel was just 29 when he umpired his first Test in December 2000 between the West Indies and his native Australia, who are in the latest cricket betting to beat India in their upcoming four-match series.

He estimates that, for each of his 13-and-a-half years at the top, he spent an average of between 60 and 70 days officiating, and another three days away for every one that he was on the field.

All in all, that added up to more than five years away from his wife and three young children.

"It's not easy and it's not for everyone," he admits.

Taufel was only looking for some "handy pocket money" when he took up a friend's invitation to enrol in an umpire's course before starting university in June 1990.

His mate, Dave, failed to achieve the 85 per cent pass mark required, but Taufel, unsurprisingly, did.

"If anything, I was always probably a little guilty of over-preparing," he says. "I'm a bit of a checklist freak."

By the time he’d reached international level, this meant reviewing and summarising six different laws every single day in order to have refreshed him memory of the full rulebook every two weeks.

He'd study bowlers, batsmen and previous series ahead of certain assignments, and attend net sessions to see teams train once he got there.

He'd then refer to previous tour notes, and read up on local airports and alternative hotels in case of setbacks. And all this was before the cricket had even started.

"I think I probably went further than most, simply because I wouldn't describe myself as a natural umpire," he says.

"I had to work harder at my game to feel that I was ready and that I deserved to have a good day out there, rather than just turn up and it be OK."

Such dedication saw Taufel win the ICC David Shepherd Umpire of the Year award for the first five years of its existence, though he's since given all but one of the trophies to people that supported him along the way.

"I did feel embarrassed and uncomfortable with those awards," he says, "because umpiring is a team sport and we were singling out one person."

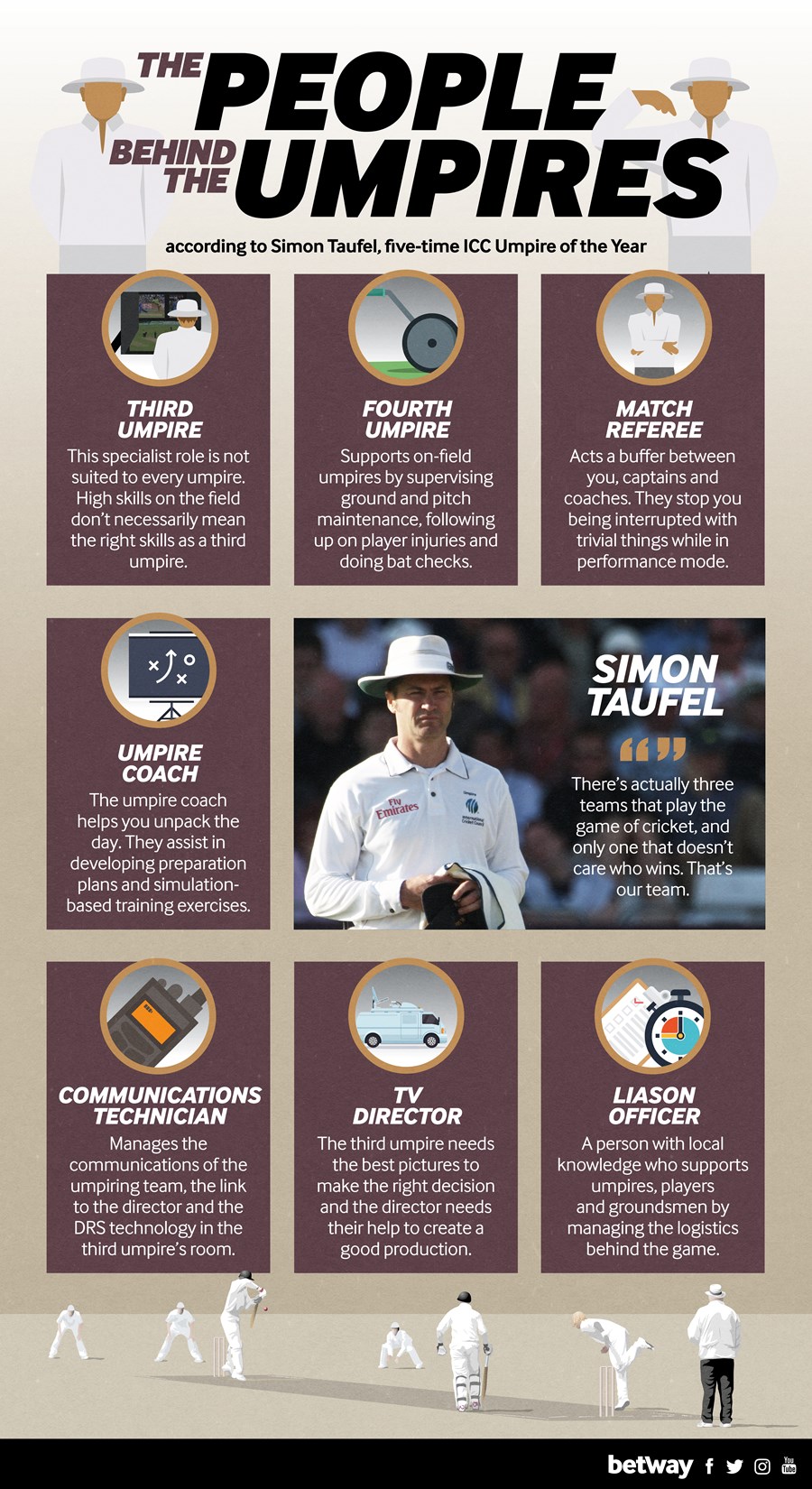

Talking to Taufel, the importance of teamwork between umpires is a recurring theme.

After retiring from the field in 2012, he moved upstairs to work as the ICC Umpire Performance and Training Manager, where he oversaw the development and implementation of additional resources to support those on the field and in the television booth, including the deployment of umpire coaches to all international matches.

“If I did my career again, I would probably want to talk more about my mistakes," he says.

"To share my shortcomings more with my colleagues after a day's play, rather than keep them to myself and have to deal with them on your own in your hotel room."

You'd think the introduction of DRS to overturn any glaring errors would have helped ease that burden, but Taufel – who experienced nine years without the support of technology and four more with it – isn't so sure.

“I don't think DRS has necessarily made umpiring easier or more difficult," he says. "It's just made it different."

“Pre-DRS, you'd deal with the error later. With DRS, you've got to deal with it at the time.

“You hear your decision dissected in your ear piece, in front of millions of people, and then, after 90 seconds, two minutes, you have to publicly change your decision and somehow regather your thoughts.

“You can feel a bit embarrassed and humiliated. It's really tough to move on and focus on that next delivery.”

As was made clear in March this year, when Australian batsman Cameron Bancroft was caught using sandpaper to alter the condition of the ball in a Test match in South Africa, technology has become increasingly important not only in aiding decision-making, but also in helping to manage player behaviour.

"The third umpire, quite easily, has got the toughest job out of the whole umpiring team," explains Taufel.

"Their job is to watch the TV as their primary focus. There should be nothing that goes out to people in their lounge rooms that is missed by the third umpire.”

But, as this incident – which led to Bancroft, his captain Steve Smith and vice-captain David Warner all being banned – proved, that is not always possible.

"I think it's fair to say that nobody would have expected what happened in Cape Town to unfold before our eyes as it did.

"As much as you try to simulate different scenarios in a training environment, sometimes there are things that you just think: 'Wow, is this really happening?'"

Taufel was working for Cricket Australia, in charge of umpire selection and match referee management, at the time, and has sympathy for officials that are put in that position.

"The game of cricket is now more commercialised. It's a different type of animal at Test and international level.”

"There are a lot of people who push the envelope to try to get the result to go their own way.

"I've got no problem with players playing the game hard, no problem at all," says Taufel, who captained his first XI at secondary school before going on to play for New South Wales Schoolboys Under-19s alongside Adam Gilchrist and Michael Slater.

He laughs. “I played the game pretty hard. I appealed for just about everything I could. I don't think I ever got into trouble with the umpires, but I do remember getting a bit of a bollocking from my coach for swearing on the field.

“For me, behaviour is a captain, a coach and a team issue. At the moment, people seem to abrogate that responsibility of managing player behaviour through code of conduct or umpires.”

Yet Taufel, who remains the only umpire to have ever been invited to give the MCC Spirit of Cricket Cowdrey lecture, believes that the episode can serve as a turning point for the game as a whole.

“I hold the spirit of cricket close to my heart. Results come and go, but who we are and how we play really defines us.

“We are guardians of the game of cricket. We have to leave it in good shape for the next generation.

“The only way that we can do that is through adherence to the laws and to the spirit of that game.”

This is where Taufel believes that players and coaches can learn from umpires.

“You can't change what's already happened, it's part of history now."

"But, like a cricket umpire who can't change the ball that’s already gone, you can certainly do your best to get the next decision right,” he says.

“That's what I would say to Australian cricket and that's what I would say to the global game: learn from what's happened and use the opportunity to make the game stronger than it's ever been before.

"That's something that everyone can look at. Not just one country or one player or one captain, it's up to everyone to play their role."