Why don't we consider Jimmy Anderson a British sporting icon?

The fast bowler's career hasn't conformed to the usual narratives, but he still deserves to be recognised as one of our greatest ever sportspeople.

England's "best ever" cricketer

Five-hundred-and-seventy-five wickets and counting.

More Test match dismissals than any England player in history. And more than any fast bowler, anywhere and at any time.

Jimmy Anderson has not only conquered England, but the world. Since his debut in May 2003, only India's Zaheer Khan has taken more wickets away from home.

On home soil, though, he is the king. His 368 wickets in his own country, where conditions suit the way he likes to swing the ball, dwarfs anybody else in world cricket.

In a 16-year international career, he has won four Ashes series and guided England to become the No. 1-ranked Test team in the world in 2011.

Some argue that those numbers only display what you can achieve if you play for a long time, but that is precisely the point. Up to seven times your body weight can go through your ankle when you bowl, let alone your shoulders, hips and knees.

Anderson has sent down over 30,000 deliveries in Test cricket.

That the soon-to-be 37-year-old has kept himself in shape to play more Test matches for England than any fast bowler in history despite that physical pressure is an achievement in itself.

There is a reason why Alastair Cook described him as "the best cricketer England has ever produced" last summer.

Outside of cricket, though, Anderson isn't considered among the UK's finest sportspeople at all.

In the Telegraph's top 100 British sportspeople of 2016, when he was already England's leading wicket-taker, he finished 84th, beaten by 33 different 21st-century sportspeople and nine other English cricketers.

So why is it that England's "best cricketer" is not popular enough to compete with Andrew Flintoff and Ian Botham in such a contest, let alone Andy Murray, Steve Redgrave and Mo Farah?

We assess the criteria that defines them, but not Anderson.

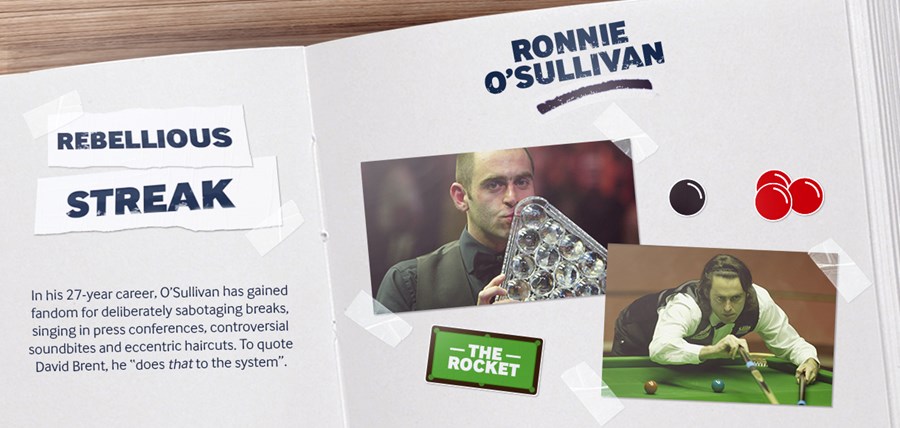

Rebellious streak

When he broke into the team in 2003, Anderson seemed set to emulate Ian Botham as English cricket's newest rebel.

Aside from the bolshy attitude and exuberant wicket celebrations, the Lancastrian wore a Kevin Pietersen-esque streak of red down his Mohican. But it is telling that Pietersen, who sported the same hairstyle after Anderson, is remembered for it more.

After time out of the side, Anderson returned in 2005 as a more understated character, with a conventional hairdo. Much more cricket.

To this day, Anderson is prone to grumpiness at a misfield, or a chunter at an umpire, but rarely with malicious intent. He is certainly not anti-establishment.

Unlike Ronnie O'Sullivan, Lewis Hamilton or even Pietersen, whose reputations were enhanced by sticking their middle finger up at their own governing bodies.

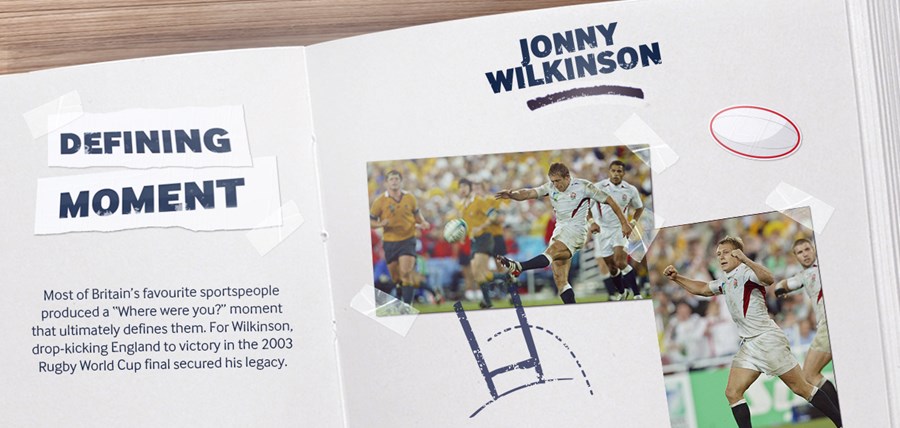

Defining moment

Most of Britain's favourite sportspeople produced a "Where were you?" moment that ultimately defines them.

For Jonny Wilkinson, drop-kicking England to victory in the 2003 Rugby World Cup final secured his legacy, despite the fact he went on to achieve little else in an England shirt.

Mo Farah, Jessica Ennis-Hill and Greg Rutherford will forever be fondly remembered for their role in 'Super Saturday' at the 2012 Olympics, while ripping through the Australian batting line-up at Trent Bridge in the 2015 Ashes will always be synonymous with Stuart Broad's career.

Anderson has never taken eight wickets in an innings, let alone 8/15 in a decisive Ashes Test match, like his long-term opening bowling partner. The latter has also taken six wickets in an innings 11 times, compared to Anderson's five.

Reliability is probably more valuable, yet it also means that Anderson's career has never been associated with one moment of heroism.

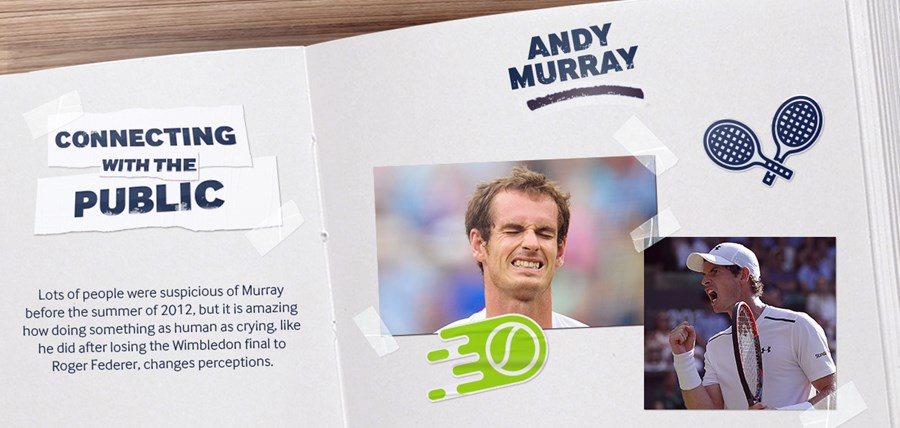

Connecting with the public

Anderson has teared up in a post-match interview more than once, but never in front of 20 million people on prime time BBC One.

Lots of people were suspicious of Andy Murray before the summer of 2012, but it is amazing how doing something as human as crying, like he did after losing the Wimbledon final to Roger Federer, changes perceptions.

From then on, Murray's personality and deadpan humour were embraced. He was celebrated as he won Olympic gold, the US Open and Wimbledon in the next 12 months.

Anderson is shy, preferring to express himself through his bowling, so his similarly dry sense of humour and fun is underappreciated.

In Swanny's Ashes Video Diary – Graeme Swann's depiction of the 2010/11 Ashes tour – Anderson's straight face provided plenty of humorous moments, but Swann's larger-than-life personality took the limelight. Anderson also features in a popular cricket podcast, The Tailenders.

Ultimately, though, Test cricket's drama is dragged out over four or five days, where individual moments of joy and despair can get lost in the undulations of the whole story. Other sports provide more impactful emotional bursts.

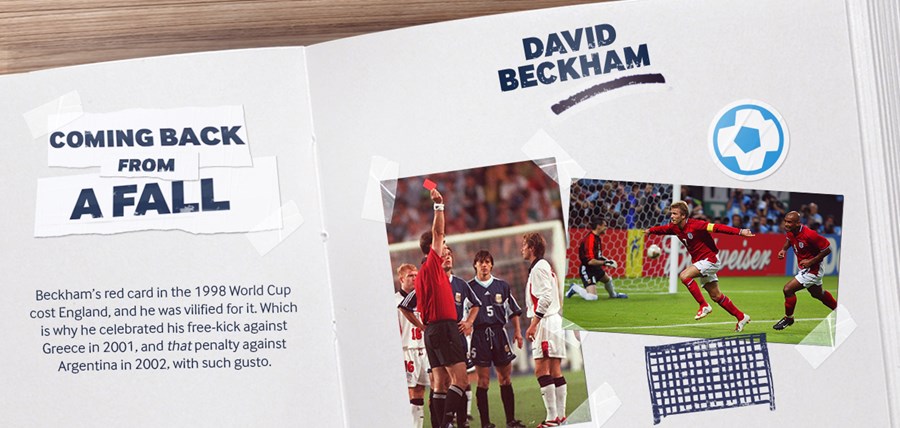

Coming back from a fall

The road to redemption: the most cliched, yet well-trodden, route to becoming a British sporting hero. The type that they make films about.

Take David Beckham, probably the greatest British sporting icon to emerge in the last 20 years.

His red card against Argentina in the 1998 World Cup cost England, and he was vilified for it. But over the next four years he redeemed himself, which is why he celebrated his free-kick against Greece in 2001, and that penalty against Argentina in 2002, with such gusto.

He's not British, but Tiger Woods felt the same surge of affection when he won the Masters in April. Even Ben Stokes – man of the match in England's epic World Cup victory earlier this summer – will likely receive the same treatment.

Anderson's career – never tainted by scandal or wrongdoing – lacks a narrative, or a Hollywood fall and rise that the public can latch onto.

Free-to-air TV

The merits of cricket being hidden behind a paywall is heavily debated, but fewer eyeballs have witnessed Anderson's brilliance than they would have had he been broadcast more on the terrestrial television channels.

He has played 138 of his 148 Test matches – and taken 542 of his 575 Test wickets – in matches televised by Sky, where viewing figures are restricted.

The last live international cricket available on free-to-air TV in this country before this year's World Cup final was the 2005 Ashes, when it could be argued that the last batch of cricketing cult heroes – Pietersen, Flintoff et al – were formed.

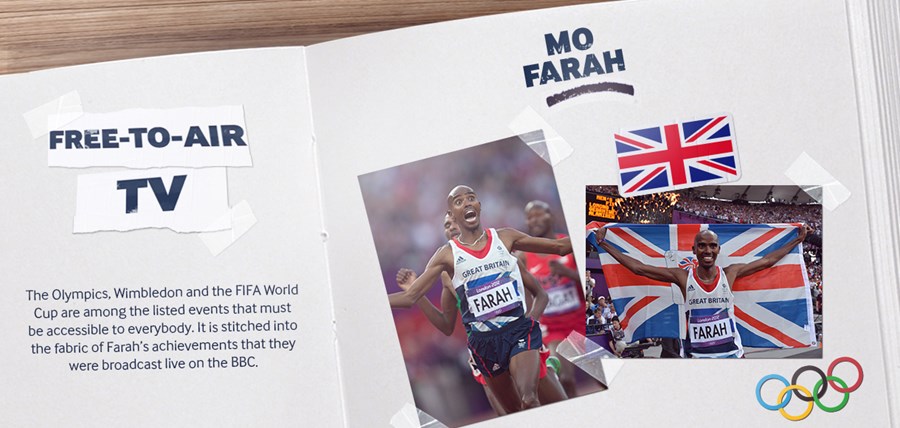

The Olympics, Wimbledon and the FIFA World Cup are among the listed events that must legally be accessible to everybody.

It is stitched into the fabric of Murray and Farah's achievements that they were broadcast live on the BBC, where everybody could watch them. Anderson has not enjoyed that privilege.

So is Anderson underrated?

The fact that Anderson isn't considered a British sporting great means our perception of greatness probably needs redefining.

Patience, consistency and longevity – not that they are words that do Anderson anywhere near full justice – are unsexy traits.

But that someone of his prodigious skill is not appreciated as much as he deserves to be shows that the British public are looking for something far beyond ability.

Exposure is vital. Millions of sports fans have hardly ever seen Anderson live, so can't be expected to treat him with much reverence.

And not that he will mind, but an understated personality and limited back story does not lend itself to becoming a cult hero.

Perhaps yet another Ashes-winning campaign, surely Anderson's last, will enhance his reputation beyond cricket.

If not, the country's finest bowler will continue to be undervalued.

Visit Betway's cricket betting page.