How important are match-going football fans?

With mass gatherings off the agenda, a former England international and football finance expert explain the influence match-going fans can have.

The 12th man, the difference-makers or just part of the furniture.

Match-going football fans are an inescapable part of the sport, from the racket they make to the money they spend.

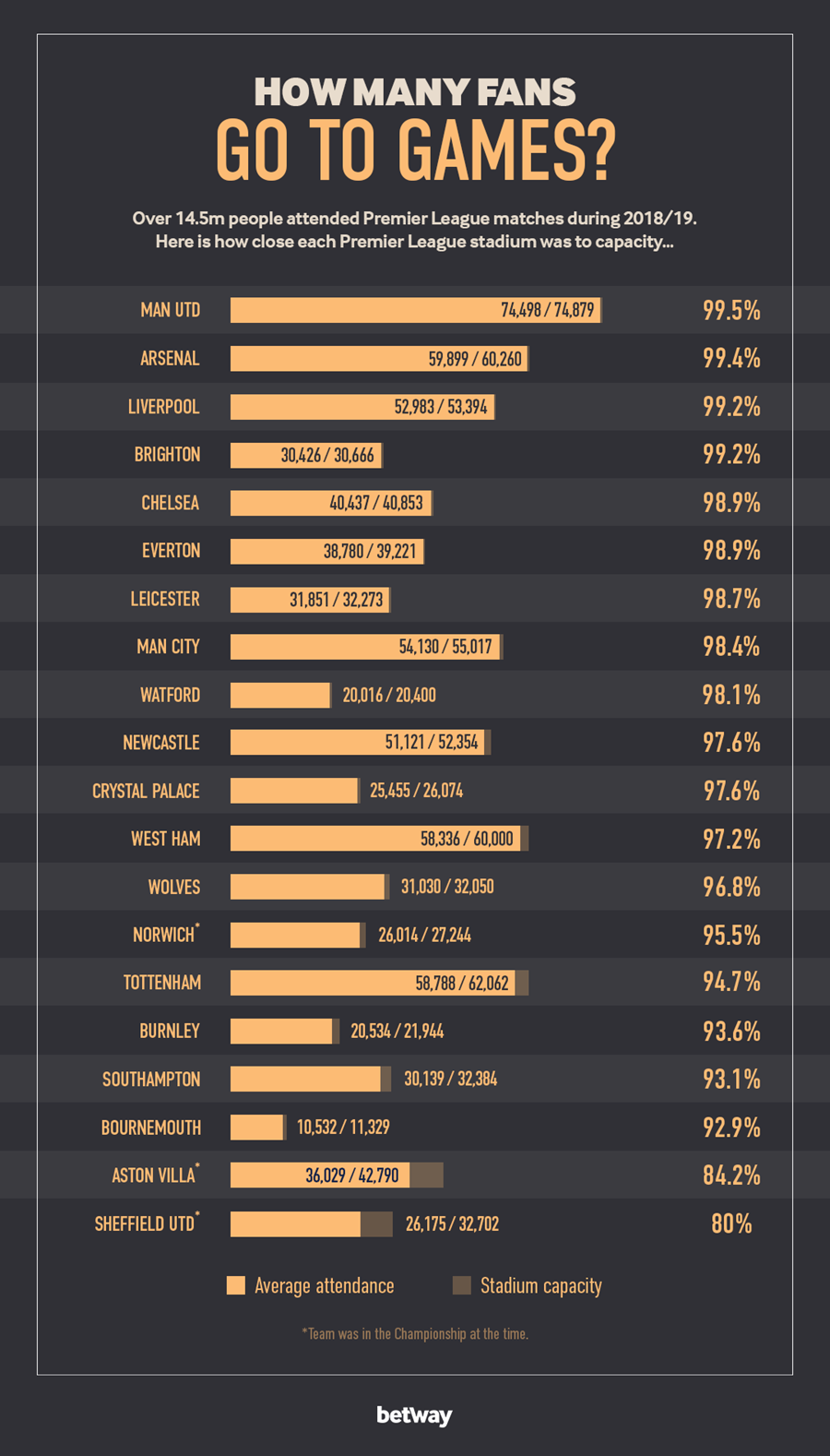

During the 2018/19 season, the average attendance at a Premier League game was 38,168, while more than 14.5m people clicked through the turnstiles overall.

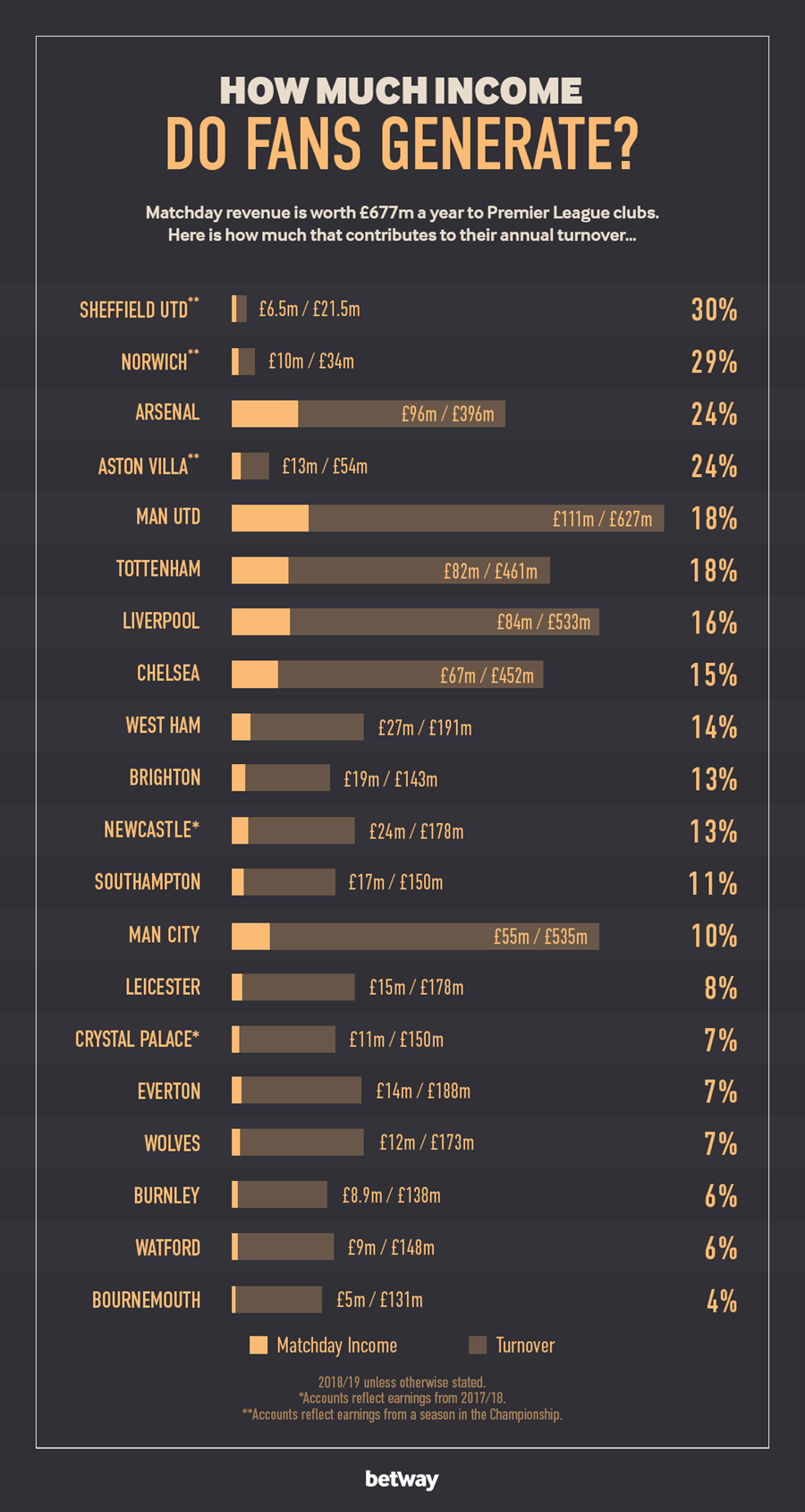

That translates into a total figure of £677m brought in by fans on a matchday.

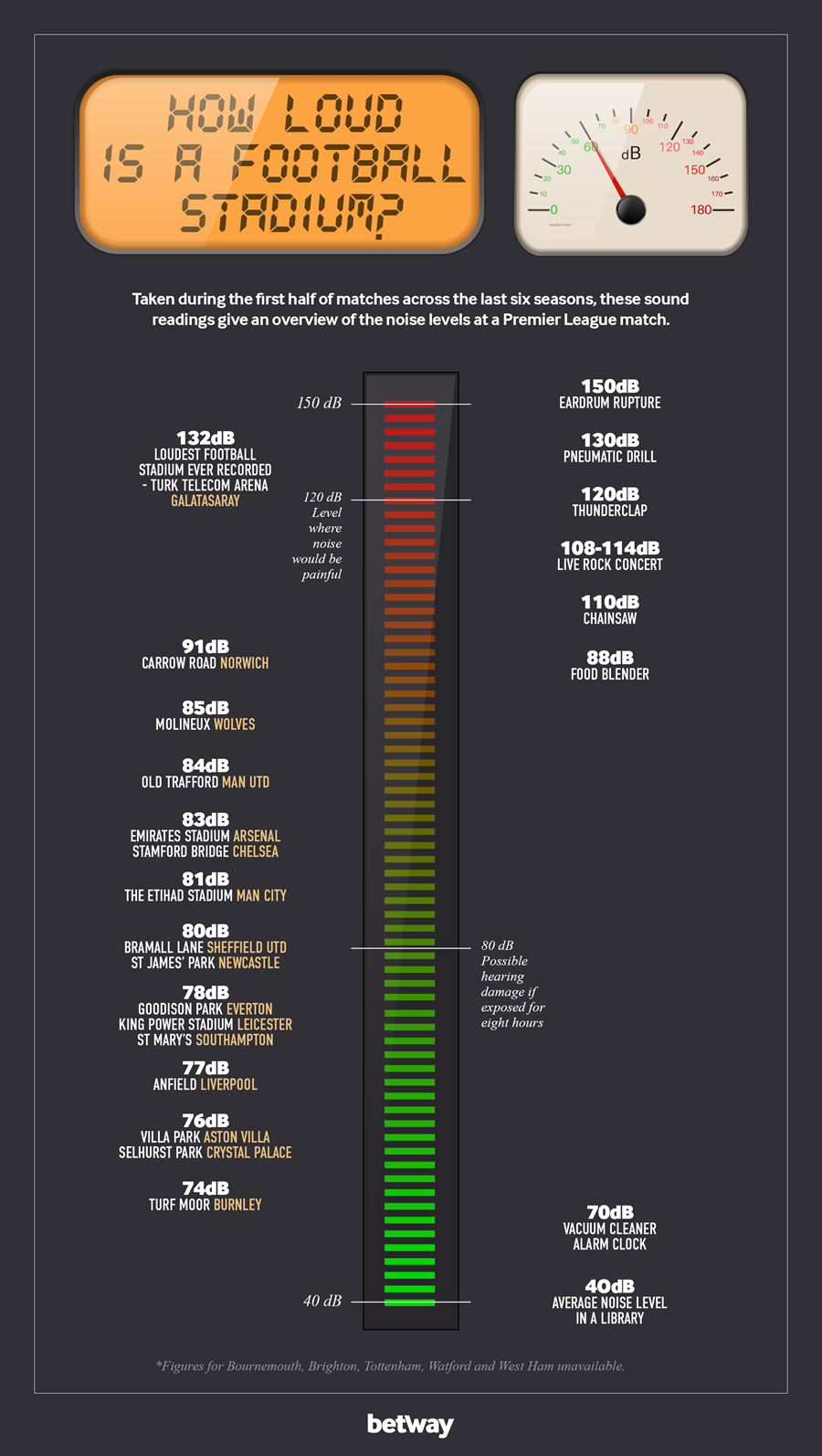

The volume they generate, meanwhile, can be louder than a live rock concert or standing next to a pneumatic drill – easily loud enough to hurt your eardrums and damage your hearing.

But with mass gatherings off the agenda until further notice, stadiums that normally hold thousands of fans will lie empty when football returns to the top flight.

It is a new normal that will take some getting used to.

The Bundesliga, in which Dortmund are odds-on for a top-four spot in Betway's football betting, resumed in May and the absence of those fans who would normally be in attendance has been conspicuous.

Taking place in a cavernous bowl of empty seats, it is a version of competitive football that has been akin to an art gallery without any paintings – you recognise the setting but something important is missing.

“To go from playing in a full stadium to playing behind closed doors is eerie,” says former West Ham captain Alvin Martin.

“The atmosphere that you’re reliant on isn’t there and you can’t feed off the energy of the crowd.”

Martin was part of the West Ham team that beat Arsenal in the 1980 FA Cup final and their subsequent European Cup Winners’ Cup campaign the following season.

The defender played in both legs of their first-round tie against Spanish side Castilla, the first of which was held at the Bernabeu.

West Ham lost 3-1 and, after fan trouble in Madrid, UEFA ordered the return fixture at the Boleyn Ground be held with no supporters present.

“You could hear every word that was being said,” says Martin.

“In fact, we even got a knock on the dressing room door during our half-time team talk with John Lyall.

“It was one of the directors who had been sent down to ask if we could keep the industrial language to a minimum.”

Despite their ticking off, West Ham went on to win the game 5-1 on the night and 6-4 on aggregate to progress to the next round.

Martin was much more accustomed to playing in front of a packed stadium.

The defender earned 17 caps for England and is fifth on West Ham’s list of all-time appearance makers after playing 596 times for the club over an 18-year period.

“At West Ham, the fans created an atmosphere that was up there with the very, very best,” he says.

“They are the ones that you play for. When they turn up at a game, they set the stage for you.

“They enhance the feeling of the game and the worth of it. You know that if you're playing in front of 30 or 40,000 people then you're doing something important.”

It is easy to understand how supporters can play a major role in the performance of their team.

Their vocal backing and the extra responsibility that comes from playing in front of a passionate can elevate a player’s performance.

“Those big atmospheres help give you an extra five or 10 per cent that you can’t replicate in training,” says Martin.

“They make you nervous, which I think is a very healthy thing for a sportsperson. When you're nervous, that's when you perform your best.

“If you go in for a tackle and there's a crowd roaring for you and willing you to win it, I think inevitably it puts a little bit more onto you.

“Similarly, when the crowd produce that enormous roar when a goal goes in, it gives you a lift.”

The lift that Martin is talking about – the psychological boost a player gets from the energy of a crowd – is not just limited to in-game performance.

The hectic schedule of a professional footballer means they are normally required to play over 50 games a season and sometimes juggle both weekend and midweek fixtures.

Unsurprisingly, the physical exertions that come with the territory of their job can often lead to them playing through injuries that they pick up along the way.

But, as Martin recalls, the buzz that comes from a football crowd also has the power to help someone play through the pain barrier.

“I remember a time under Harry Redknapp when I had three injuries in quick succession,” he says.

“For two or three weeks I was playing with a fractured elbow, fractured hand and a nasty gash on my head.

“One day, I was doing the warm-up at the Boleyn and thought: ‘I’m not going to be able to play here, I'm in a lot of pain.’

“But as soon as the dressing room bell went and I knew that we were going out on the pitch, it gave me a kick of adrenaline.”

The influence of match-going fans isn’t just limited to matters on the pitch either.

The £677m generated by matchday income in the Premier League in 2018/19 works out at 13 per cent of the overall turnover for all 20 clubs.

In other words, £1 in every seven is made from fans.

While that might not sound like a significant proportion of income on the surface, it is a source of cash that clubs cannot afford to write off.

“If you talk to anybody – it doesn't matter the nature of their business – if you’re getting these regular streams of revenue, then you would be foolhardy to throw any of those away,” says football finance expert Kieran Maguire.

Of course, the total sum is not distributed evenly between each Premier League club – the bigger teams with bigger stadiums make more than the smaller teams.

For the 2018/19 season, Manchester United made £111m from matchday income – 18 per cent of their £627m turnover.

Bournemouth, on the other hand, had a turnover of £131m, of which only £5m came from match days. But even for the Cherries, that sum is invaluable.

“£5m is still £5m,” says Maguire, who lectures at the University of Liverpool and authored The Price of Football.

“Over the course of a season for Bournemouth, the money from a matchday will pay for the wages of two players.

“You can't keep on writing a cheque for £5m a month, even if you have got a decent amount of money in the bank to begin with.

“But Bournemouth lost £27m last season, so you add the loss of matchday income to that and it can only make the situation worse.”

It is essential, then, that in the absence of match-going fans, clubs attempt to come up with alternative revenue streams to cover the shortfall.

“They will be trying to claw that back in some shape or form,” says Maguire.

“I think football might have to re-invent its relationship with fans in terms of its ability to offer an experience.

“Those clubs with good lines of communication to their fans will be successful, they will work hard to engage with them.

“The industry is big, but it’s got to innovate.”

Should the sport fail to adapt, then he is clear about the future that could lay ahead.

“Clubs have got such high fixed costs and they might have to think of ways they can cut back.

“The return to some form of live action is essential. I’m not trying to be sensationalist.”

The integral relationship between football and fans is something that is not lost on Martin either.

“If you think about it, the game would not have been around for hundreds of years if people didn't love to go to matches,” he says.

“The community that is created and the people that are so passionately attached to their clubs wouldn't exist.

“That is the power that a crowd can have.”