How the Pro Kabaddi League is competing with the IPL in India

The Pro Kabddi League has gone from strength to strength since its inception in 2014, and is now keeping pace with cricket and football.

Though there are various theories about its ancient origins, kabaddi only emerged as a competitive sport in the 1920s.

It featured at the Indian Olympics and the Asian Games in the 20th century, albeit without much fanfare.

The breakthrough that truly put kabaddi in a position to compete with India’s most popular sports, notably cricket, didn’t come until the 2006 World Cup – when TV personality Charu Sharma, the director of Mashal Sports, spotted its potential.

By 2014, Mashal Sports, in conjunction with broadcaster Star Sports, had organised the latest addition to India’s catalogue of franchise-based sports leagues: the Pro Kabaddi League (PKL).

The model has seen the PKL transform kabaddi into a commercially-viable, exciting game, watched by hundreds of millions people in India.

Though it is tricky to genuinely compete with the world's biggest cricket league, the Indian Premier League, which Mumbai Indians are favourite to win in 2021 in the latest online betting, the PKL’s remarkable success means that those conversations are inevitable.

With the Indian Super League, the country’s franchise football league, also flourishing, there is now healthy competition between all of India’s leading sports.

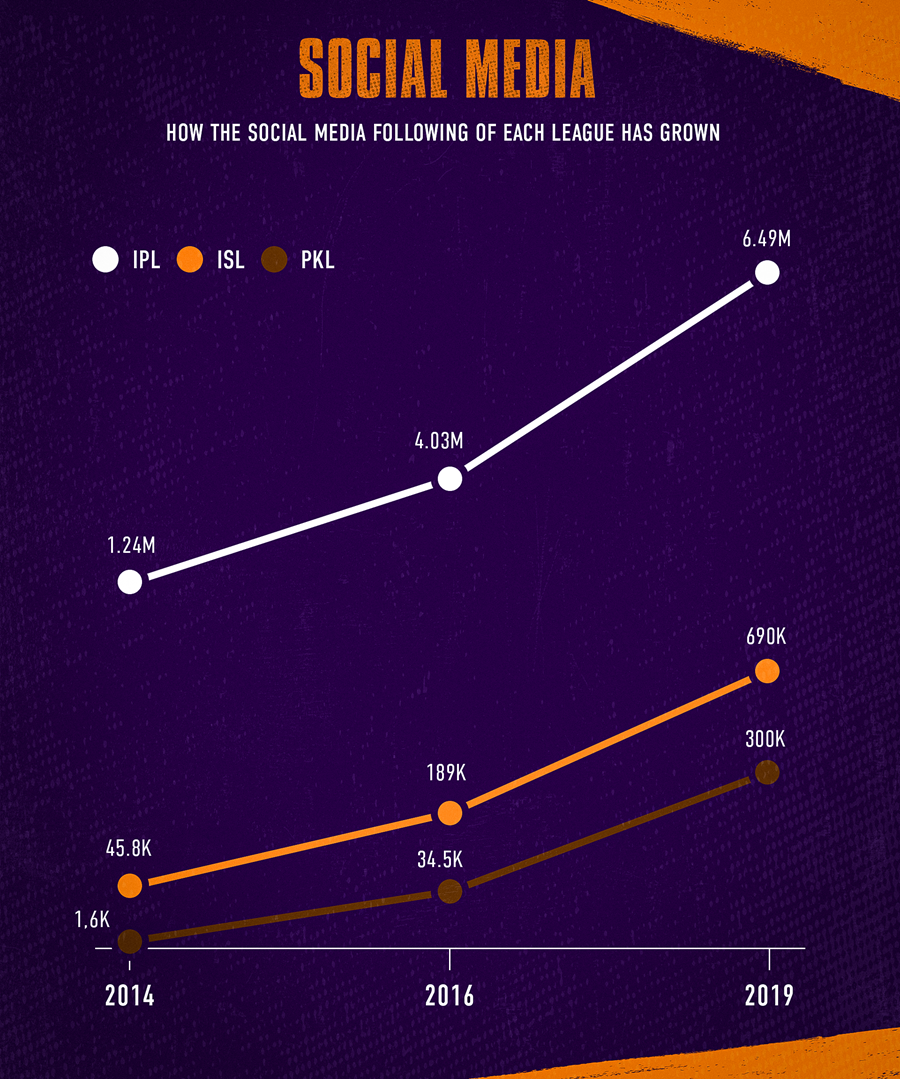

Social media

There are, naturally, certain statistics that only serve to prove the IPL’s dominance over the other two.

The cricket league features the best cricketers with the biggest pull on the planet and has a global appeal – something that the PKL does not.

It also had a six-year head start on the other two leagues, so its stark lead in terms of Twitter followers is no surprise.

Still, decontextualised from the IPL, the PKL’s following of over 300k on Twitter is impressive.

Unlike football (the ISL had around 690k followers in 2019), kabaddi is hardly followed outside India, with the sport never having had a major league as big as this one with which to develop a following.

There is also plenty of evidence that the PKL is much closer to the IPL in terms of popularity in India than those social media numbers suggest.

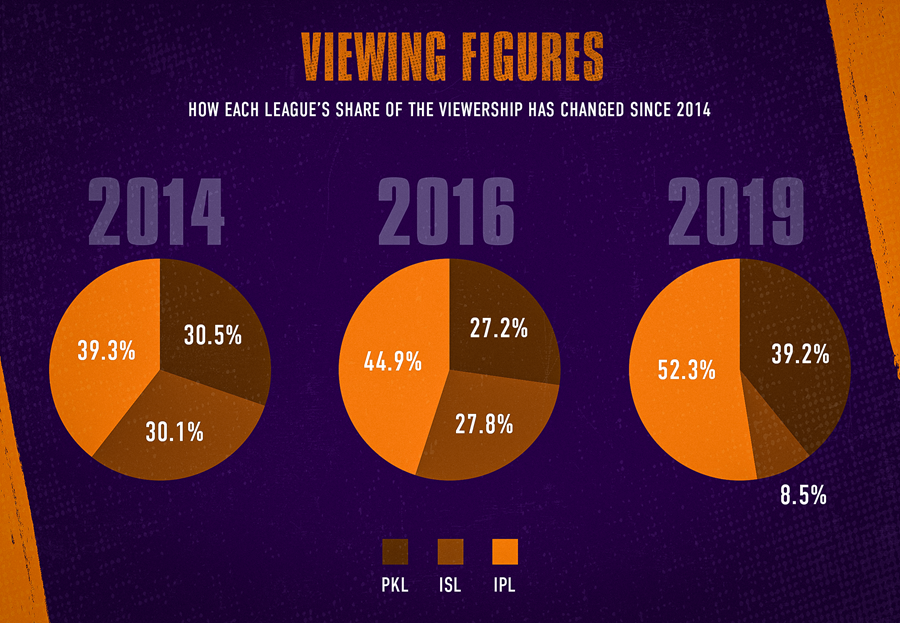

Viewership

There was general astonishment when it was announced at the end of the PKL’s first season in 2014 that it had amassed a total of 435m viewers, with the final alone watched by 86.4m.

The IPL had been viewed by 560m months earlier, hardly a landslide victory, with the ISL viewed by just 429m in its inaugural season in the same year.

Even more remarkably, the numbers have proved to be no flash in the pan.

Broadcasters Star Sports had already proved themselves to be superb television marketers, playing a huge role in the growth of the IPL, and pulled out all the stops – short, sharp explainer videos, laser shows and even encouraging players to sharpen up their image with a haircut or tattoo – in order to raise the profile of the PKL ahead of its debut.

The seeds that were sown ahead of Season 1 have borne fruit since. TV viewership for kabaddi – a sport that millions of people had never watched nor taken an interest in – is now easily beating football and is not far off cricket.

Season 4 of the PKL, the second edition of the event to be played in 2016, saw a reported 51% increase in viewership on Season 1 (the number had risen for each season in between).

Even when the popularity of the PKL has been threatened, the foundations laid by Star Sports in 2014 have carried it through.

In 2018, Season 6 of the PKL was pushed back from its usual July-October slot to October-January in order to facilitate the Asian Games and Kabaddi Masters.

Audience fatigue combined with the league clashing with India’s home cricket season meant that viewership dipped for the first time – but that dip didn’t last long.

The league regained momentum in 2019, blowing the ISL out of the water with 1.2bn impressions (a slightly different metric to viewership) to ensure that its long-term trajectory remains remarkably positive.

Though the 2020 edition was postponed, there must be some confidence that the PKL is now so engrained that viewers will remain engaged.

Finances

The emphasis on promoting the sport as a spectacle means that the cult of the individual does not seem to exist as much in the PKL as it does in the IPL or ISL.

The ISL’s recruitment system is different to the other two, but the fact that each team picks a marquee player ahead of each campaign says a lot about a competition in which the involvement of high-profile legends is fundamental.

The same, to some extent, goes for the IPL. Support for each city’s team is huge, but it would not have made the same impact without cherished individuals such as MS Dhoni, Yuvraj Singh and Virat Kohli.

The PKL has established itself as a headline competition without those big names to market the game around. Players’ profiles have grown over time, rather than the league latching onto them from the beginning.

To a degree, this explains the relatively low valuations of the most expensive players at auction when compared to the IPL, particularly in the league’s first few seasons.

As the financial might of the league has grown, and the players have begun to establish themselves as nationwide stars, so the values have crept up – not to the same extent as the IPL, but closer.

How the value of the league has improved – in terms of sponsorship and investment – is further testament to the marketing efforts of Star Sports and other organisers ahead of the inaugural season of the competition.

In 2017, Saumya Khaitan, CEO of DoIT Sports Management, owners of Dabang Delhi, described the decision to invest in 2014 as “very simple”, citing the clear vision for the league, but it still took him and several other team owners to help get the idea off the ground.

It is expected that initial investors will only have begun to turn a profit in 2017 or 2018, but their vision has been realised.

In 2016, when two seasons of the PKL were staged, the league brought in 62 crore from team sponsorship and 122 crore from on-ground sponsorship.

The commercial side of the league went to a new level for Season 5 of the competition, when VIVO come on board as title sponsors in the biggest non-cricket deal in the history of Indian sport. The prize money was then hiked up to 8 crores – a level that it has remained at until now.

Even though the increase has slowed, further testament to the PKL’s commercial viability is that several key sponsors retained their deals with the league in 2019, despite the fact that its four-month campaign directly followed the Cricket World Cup, which was their primary focus.

Despite the ongoing dominance of cricket in India, the PKL can now easily claim to be the second-most popular sporting competition in the country.

And with the league’s viewership and sponsorship deals at least keeping pace with the IPL, despite all its clear disadvantages, it is possible that there is plenty of further growth to come.