Dave Stieb on sticky stuff, bat flips, and his Cy Young snubs

Source: Getty Images

Source: Getty Images

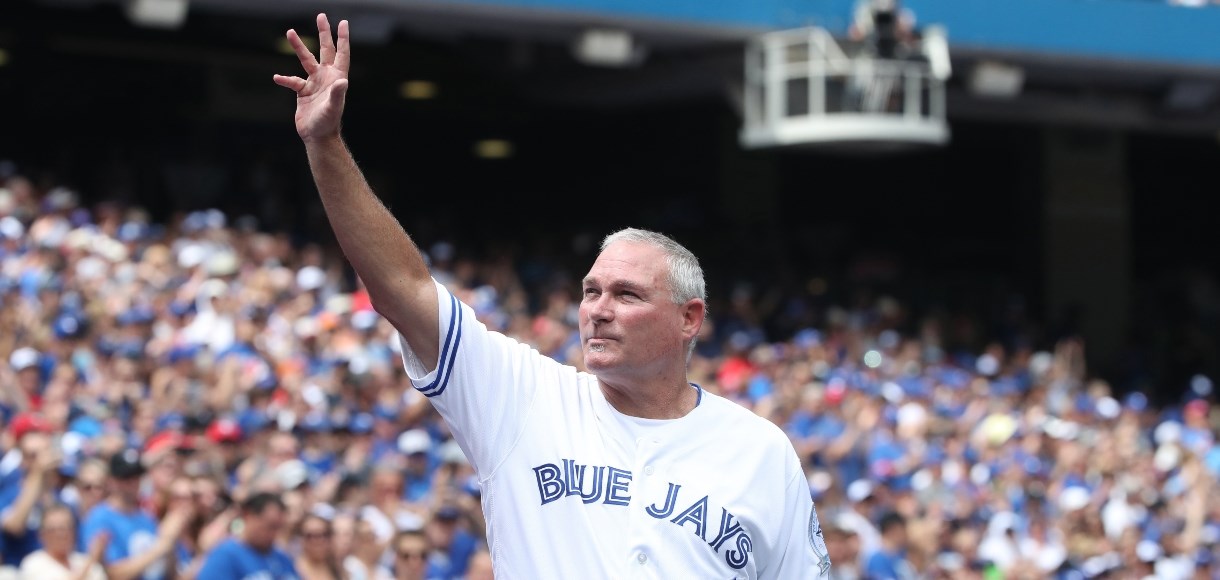

The former Toronto Blue Jays pitcher reveals his views on the modern game and reflects on his 16-year MLB career.

Visit Betway for the latest sports betting odds.

Dave Stieb knows what it takes to be a great pitcher.

The Toronto Blue Jays legend was one of MLB’s most dominant arms during the 1980s, racking up 176 career wins and being named an All-Star on seven occasions.

Although he has stepped away from baseball since retirement in 1998, Stieb still keeps close tabs on the modern game, and likes what he sees from the current crop of pitching talent.

“Look at Scherzer, Gerrit Cole, deGrom, Bieber, Buehler. These guys – just wow.” he says.

“Without overstating it, they’re devastating. I’d love to say I threw like them when I was playing, but these guys just seem way better than me.”

While he may play himself down, the truth is that Stieb does see some part of himself in all of those players.

A right-handed power pitcher, Stieb was initially known for his fastball before developing an effective breaking ball repertoire that included one of the nastiest sliders in the game.

“I identify with pretty much all those guys,” he explains. “They’re right-handers who throw hard with nasty stuff, and can dominate a game at any given time.

“That’s what I see in them and that’s how I felt when I pitched.”

One thing that does separate modern-day pitchers from those who played in Stieb’s era is velocity, with 100mph fastballs now a daily occurrence in the majors.

Stieb isn’t convinced things are as different as they seem, though.

“The thing is, the radar guns when I pitched weren’t as accurate as they are now,” he says. “That’s why everyone is throwing 99, 100.

“In my day I was throwing 92 to 95, 96, so I have to believe that if I used one of these guns back then I would have been clocked at 100.

“It just makes it more sensationalised now with these guys throwing 101, 102. It makes them seem like Superman.”

Not only are pitchers being clocked at higher speeds than ever before, but elevated spin rates also mean pitch trajectories have become more exaggerated.

A big factor in this is the widespread use of illegal sticky substances, which help pitchers grip the ball better and spin the ball more.

Many of these substances, like Spider Tack, are modern inventions that were not available to Stieb when he played.

“All I ever used was the rosin bag,” he explains. “My fingers were almost black by the end of the game because I went to it a lot to give me that grip.

“We always heard about some of the old timers using hair gel so the ball would sink, or using sandpaper or nail file to scuff it up.

“But I was never aware of anyone who I played with, or against, using anything like that.”

The use of sticky stuff has become so rampant that MLB recently cracked down on its use, implementing in-game checks by umpires and banning pitchers who break the rules.

Stieb is happy that measures are being taken against the issue, but isn’t sure things are going far enough.

“It makes sense to me to ban this stuff, because these are foreign substances,” he says.

“I do think they need to be checking pitchers when they come into the game, though. If I’m a batter and I strike out on a nasty pitch, but he gets busted for sticky stuff, I don't get my pitch back. I struck out, but he cheated.

“They should be checking pitchers when they come in the game, not after. Because that's beside the point. That's after the fact.

“It's sad that they have to even do that. You’ve got to have integrity in this game, you’ve got to have respect. You can't try to find a way to cheat and succeed.

“If you're the kind of guy that will cheat to succeed, you don't belong in baseball.”

Another aspect of the sport that has changed in recent years is the increased expression of emotion on the field.

Tune into any MLB game this season and you will see bat flips, fist pumps and wild celebrations, with MLB encouraging such behaviour among players in an attempt to appeal to younger audiences.

Stieb was no stranger to shows of emotion – he was widely known as a fierce competitor who talked to himself on the mound and berated teammates for their mistakes – but he doesn’t identify with the behaviour of current players.

“Some of the stuff is so over the top that I think it disrespects the game. It disrespects your opponents,” he says. “I know that MLB wants that kind of stuff in the game, but I'm old school and I don't care for the celebrations that go on.

“It doesn't matter if I like it or not, but I know there's a lot of other players that I played with who agree with me. We have the same attitude towards it because of the way the game was when we played it. You just didn't do that stuff.

“My biggest issue with it is what it does to Little League kids and high school kids. You don't want that stuff going on in Little League. You don't want that going on in high school. There’s not a place for that kind of behaviour at that level of baseball.

“But it is what it is. I don't like it, but they're going to do it. That's the game today.”

There are parts of the game today that Stieb likes, though.

Despite being one of the best pitchers around for much of his career, Stieb never won a Cy Young Award. He came closest in 1982, when he finished fourth in the voting.

A lack of individual awards certainly didn’t help his Hall of Fame case, as Stieb was cast from the ballot in his first year of eligibility in 2004.

Had the current level of analytics and sabermetrics been around then, however, Stieb would surely have got the awards he deserved.

“I love analytics, because it would’ve made me look better!” he says. “When I played, it was all about wins and ERA. That’s it. That’s all anybody cared about.

“One of my ex-teammates, Pat Hentgen, told me that if they’d used WAR back then, I’d have won the Cy Young four years in a row – ’82, ‘83, ‘84 and ‘85.

“I’m like ‘Wow, Pat. That’s great to hear, but that doesn’t do much for me right now. In fact, it makes me feel bad, because I didn’t even get one.’”

Stieb may get another chance at the Hall of Fame through the Modern Baseball Committee, which meets twice every five years to elect players no longer eligible through the writers’ vote.

But even if he doesn’t get that recognition, those who watched Stieb pitch know how dominant he was, and modern analytics have proved his greatness beyond any doubt. Awards or not, no one can take that away.