What impact does a crowd have on a snooker match?

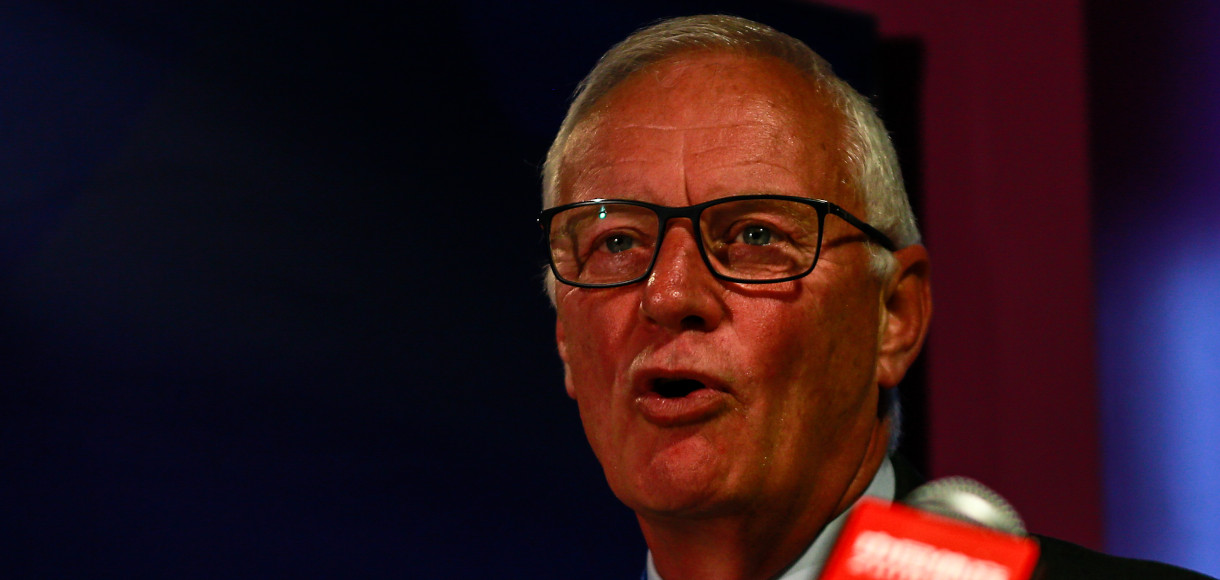

Barry Hearn, Neil Robertson, Mark Selby and Martin Gould reveal why snooker has worked behind closed doors, but call for the return of crowds as soon as possible.

When it was decided that elite sport could return behind closed doors in June 2020, World Snooker were among the quickest governing bodies to act.

Snooker, after all, is logistically possible during a pandemic. Only three people – the two players and the referee – need be in the arena and nobody needs to share equipment.

On Monday June 1 it became just the second sport to return after a 13-week hiatus, with horse racing back first by a matter of hours.

There was also an acknowledgement, though, that playing all matches in small booths in front of no supporters was not much fun for anybody.

It was a setup born of necessity, something to endure until the world got back on track.

“I didn’t enjoy the first major event back, the Tour Championship,” says two-time UK Champion Neil Robertson.

“It wasn’t great. It was the first period in which we were playing behind closed doors and not much was done in terms of making it feel like a big event.

“All you could see was the two cameras and the big curtain drawn all the way around the table. It wasn’t very inspiring.”

It’s evolved to a point where the sport has come out of this looking very attractive.

But in the following months, as players, broadcasters and viewers have become used to the arrangement, the unease has softened.

Unlike in other sports like football, the quality and results of snooker matches and tournaments does not seem to have been affected by the absence of a crowd.

Quite the opposite, in fact. The four ranking events preceding the UK Championship in the 2020/21 season have been won by Judd Trump (twice), Mark Selby and Kyren Wilson, three of the top five players in the world.

The other major event, the Champion of Champions, was won by world No. 8 Mark Allen.

Crowned by Ronnie O’Sullivan winning one of the most entertaining World Championships of all time, it’s been an excellent few months of snooker on the table.

“I was very concerned about the lack of atmosphere,” says World Snooker chairman Barry Hearn. “But it’s actually evolved to a point where, with some technical assistance and the players’ enthusiasm and passion, the sport has come out of this looking very attractive.

“Our audiences have never been so big. We are escalating. Viewers are getting involved with the matches, enjoying the sport for what it is. And the players have responded.

“I don’t think it’s been overly detrimental at all.”

Even before the pandemic made it a reality, there could be no denying that a crowd has less bearing on snooker than on the vast majority of other sports. They sit there in silence, after all.

But even with the quantity and quality of the game still intact without one, the game’s leading players still feel that something is missing.

“The atmosphere and intensity is definitely not there,” says Mark Selby. “You can be a few frames down, know that you’re not playing well, and just think, ‘You know what? I just want to get myself out of here.’

“If you’re losing in front of crowd, you keep going until the very end. The support of your family and friends can get you going.”

Selby describes winning the first ranking event of the season, the European Masters, in front of just his opponent, Martin Gould, and a TV crew as “very, very strange”.

It might have felt even more anti-climactic to Gould, who was playing in just his third ranking final.

“I was up for the final,” Gould says, “but it definitely did feel weird.

“I was allowed to have four guests with me, but it didn’t feel right. They would have had to sit in the players’ lounge and only leave if they were going outside.

“Mark didn’t have anybody ether, so in between sessions we just had a cup of tea and a chat, which you wouldn’t normally do during a final.”

The need for a crowd extends beyond making the players feel comfortable, though.

Hearn needs to balance the books and is exploring all avenues possible to make it happen.

“From a revenue perspective, we have to take into account that these are substantial hits for us as a business,” he says.

“We are constantly in dialogue with the DCMS about the latest updates.

“We are also looking into different testing technology. There is a future in a 10-minute test, I believe, where every member of the crowd has tested negative prior to them going into the arena.”

For now, everybody involved is grateful for Hearn’s efforts to get as many events on as possible, rather than, in his words, “pack up and go home for the year”.

It is worth remembering that there were supporters present on day one and for the final of the World Championship in August, too – arguably the biggest sporting event in the UK to host any form of crowd since the pandemic begun.

“When you put things into perspective, it’s been very easy to find the motivation to compete in the tournaments,” says Robertson.

“A lot of people have lost their jobs.”

Selby agrees. “Things could have been an awful lot worse,” he says. “We could have had no tournaments and no income. We have to thank World Snooker for that, really.”

For players struggling for form, like Gould, the absence of a crowd might even have been a blessing.

The world No. 31 suffered one the worst seasons of his career in the 2019/20 campaign, but playing behind closed doors has allowed him to treat matches “like a practise down at the club – you play in front of nobody there anyway”.

“I suppose there are some positives,” says Selby. “Perhaps there is less pressure and there are less distractions.

“You’ve got nobody moving, no cameras going off, no coughing.”

But the three-time world champion immediately caveats that.

“We’re a big sport and we want a crowd to thrive off. That’s what we play for, to play in front of big arenas and in front of crowds.

“The sooner that can come back the better.”

The last few months should serve as a reminder that the players’ own skill is what sustains snooker.

But just because they are largely silent, the impact of a crowd on those players also cannot be underestimated.

Visit Betway's snooker betting page.