Andy Murray's ex-psychologist on why tennis players choke

In our exclusive interview, Roberto Forzoni discusses mentally preparing the two-time Wimbledon the champion, Laura Robson and Jo Konta.

There are few non-life-threatening situations when an ordeal suffered by someone you’ve never met causes you pain.

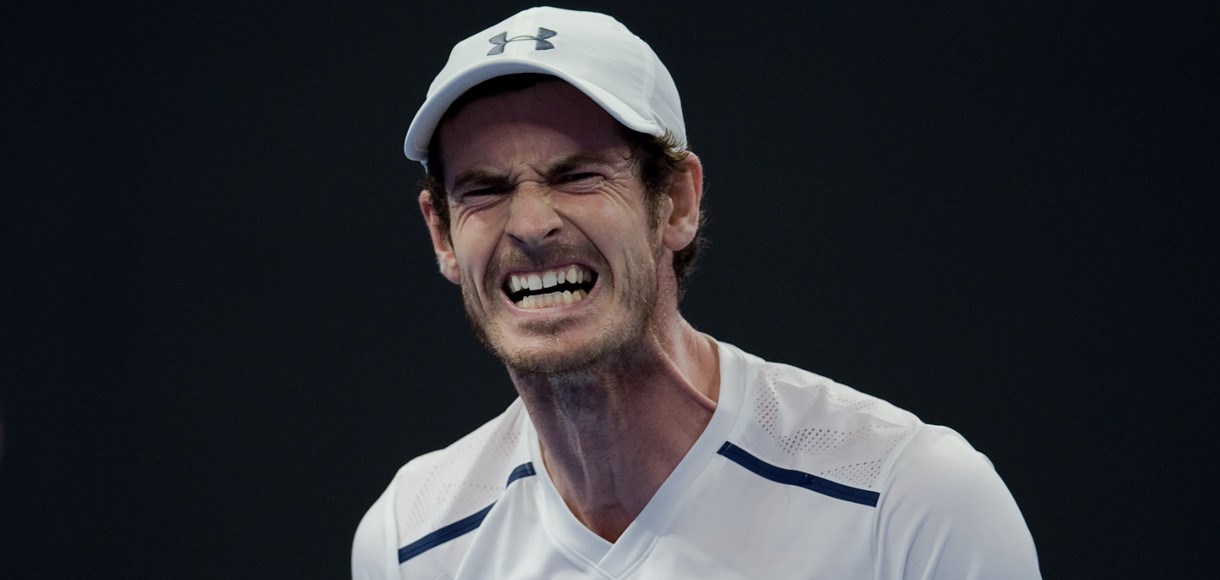

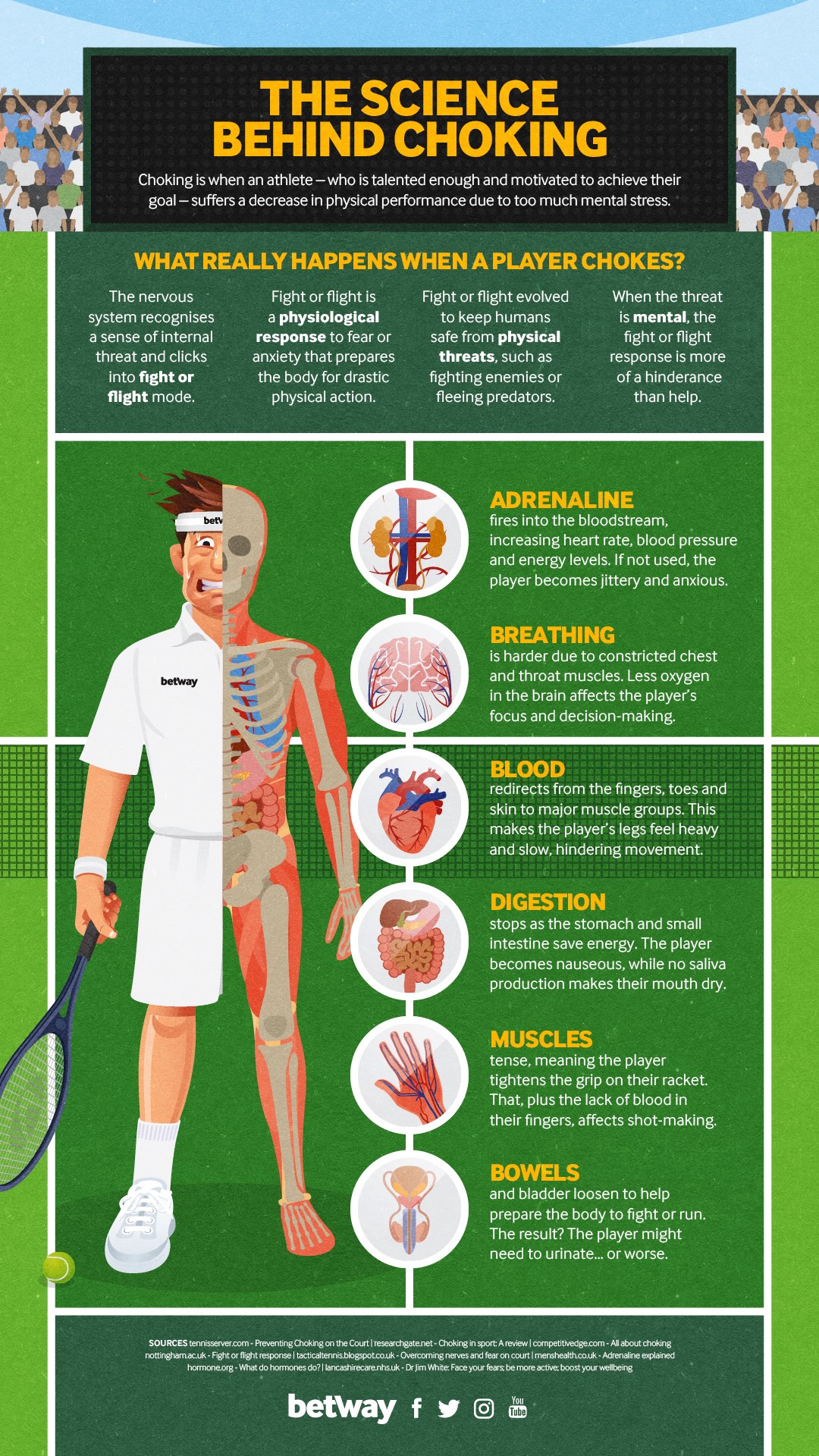

Watching a tennis player choke – or any athlete, for that matter – is one of them.

It’s a tortuous experience. You know they can perform better, and that they desperately want to. But, for some reason, they can't.

Poise, intelligence and technique are replaced by cinderblock feet, trembling limbs and crippling self-doubt, just at the vital moment.

But why does it happen?

"It’s a thought process," says sports psychologist Roberto Forzoni. "Rather than thinking about what you do, you think about the consequence."

Forzoni knows what he is talking about, having operated as the National Performance Psychologist with the Lawn Tennis Association between 2007-09.

There, he worked with Andy Murray – who is to win Wimbledon in the latest tennis betting – Laura Robson, James Ward and Jo Konta.

"You look into the ‘what-if’ scenarios. What if I miss? What if I play badly? What is someone going to say?"

Expectations – whether it be from the press, family or the player themselves – and past failure can play a part, too, explains Forzoni, who has also worked with Fabio Capello, West Ham United, the FA and a host of Olympians during his 25-year career.

Part of Forzoni’s remit at the LTA was to teach Murray and other emerging British players how to combat the choke.

For a player to do so successfully, it is imperative they remain engaged on court.

"There’s a great mantra we use: control the controllables," he says.

"Players can’t actually control the result, they can’t control the outcome of the match.

"But too often, rather than focusing on their game strategy – or a technique they’ve been working on in training – they start focusing on the scoreboard, which makes it very difficult to make any decisions."

Such as?

"If, for example, they’ve had success with a forehand down the line, but then the opponent cottons on and moves across the court, they’ve got to be able to change their strategy.

"You can only do that if you’re creative and calm in what you’re doing and thinking. That’s crucial."

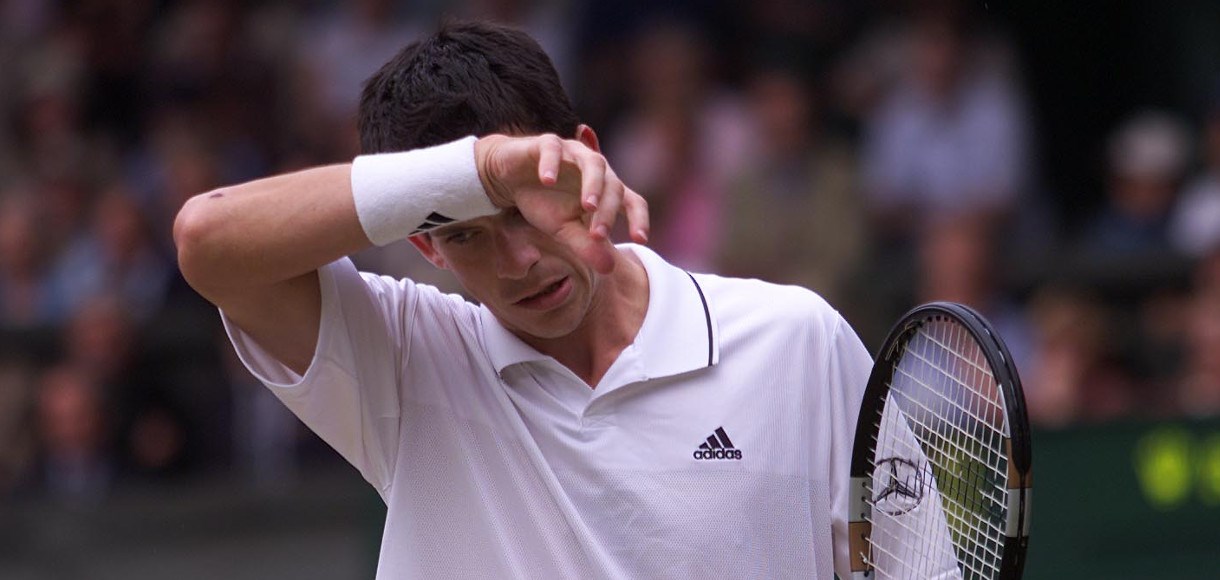

While also applying to many other sports, there is a feeling that British tennis players are more susceptible to choking than their overseas contemporaries.

Who can forget Tim Henman blowing his greatest chance to reach the Wimbledon final against Goran Ivanisevic in the 2001?

There is, however, a legitimate reason for Brits’ mental fragility.

"With a British player, it’s probably not as competitive as, say, playing in Spain or France, where the level of competition is much higher," he says.

"Footballers in this country have to be mentally tough from an early age because they’ll get released from clubs – competition is fierce.

"In tennis, it’s not as fierce. So if you’re half-talented you can become one of GB’s top players.

"That’s why a lot of them go to Spain or America to train, because they’re put into very competitive situations in training.

"They become more accustomed to accepting that things can go wrong and have the ability to come up with the solutions."

Choking was never a problem for Murray, though, who worked with Forzoni in his early twenties.

"He was young, but very good," says Forzoni. "He took things on board very quickly and learned that when he controls his emotions on court, he generally gets better results.

"Something Andy used to do was self-handicapping, where he’d rub his ankle or his back. That’s a trigger for his opponent to say: 'I've got him now.'

"So now if he starts to rub something, he will say to himself, 'No, I’m not going to do that – even if it’s hurting I’ll show that I’m OK.' That in itself takes away from the choking."

People who follow tennis all year round have always appreciated Murray’s resilience, yet casual viewers have at times accused him of choking – especially after he lost each of his first four grand slam finals.

After defeat to Roger Federer at Wimbledon in 2012 – which famously prompted post-match tears – Murray himself questioned whether he would ever win one of the sport’s major titles.

Forzoni, though, always believed that the now-three-time slam winner’s career has always been a "progress of success".

"You could draw a line from where he started to when he became the world No.1 and it just goes up," he says.

"Obviously there were some blips along the way. But he’d get to a quarter-final of a slam, then he’d get to the semi-final, then he got to the final of Wimbledon.

"Everybody was just like: 'Oh, he’s a choker, he’s never going to do it.' But he was improving every year.

"You knew the next time he was in the final it wouldn’t be such a big event. He probably couldn’t wait to get back into the final."

Murray, of course, bounced back from that 2012 defeat at SW19 by winning Olympic gold in London and the US Open later that summer.

"And so it goes on, doesn’t it?," says Forzoni. "He wins one, he wins two. Because he had the sense to look at his progress, and not believe the hype that he was a choker."

If Murray retired tomorrow, even his fiercest detractor could not say he has not fulfilled his potential.

But have the on-court tantrums that have always been a part of Murray’s game held him back at all?

"Different players act in different ways," says Forzoni, diplomatically.

"The difference is that if Andy does have a little outburst, he’s got the ability to get back to where he needs to be very quickly. That’s where a player’s routines will come into play.

"Previously, people used to see John McEnroe blow up on court and say: 'That’s OK, I can do that.' But what they didn’t have was his ability to get right back.

"So Andy can do that now. He can blow up. And Team Murray will accept it, and know how to respond."

Sending pelters at your players’ box can’t ever be advisable, though, can it?

Forzoni pauses for a second.

"I’ve got to say, when he doesn’t do it, he plays better overall."

*This article was originally published in June 2017