The harsh reality of the UFC: ‘Most fighters barely make money’

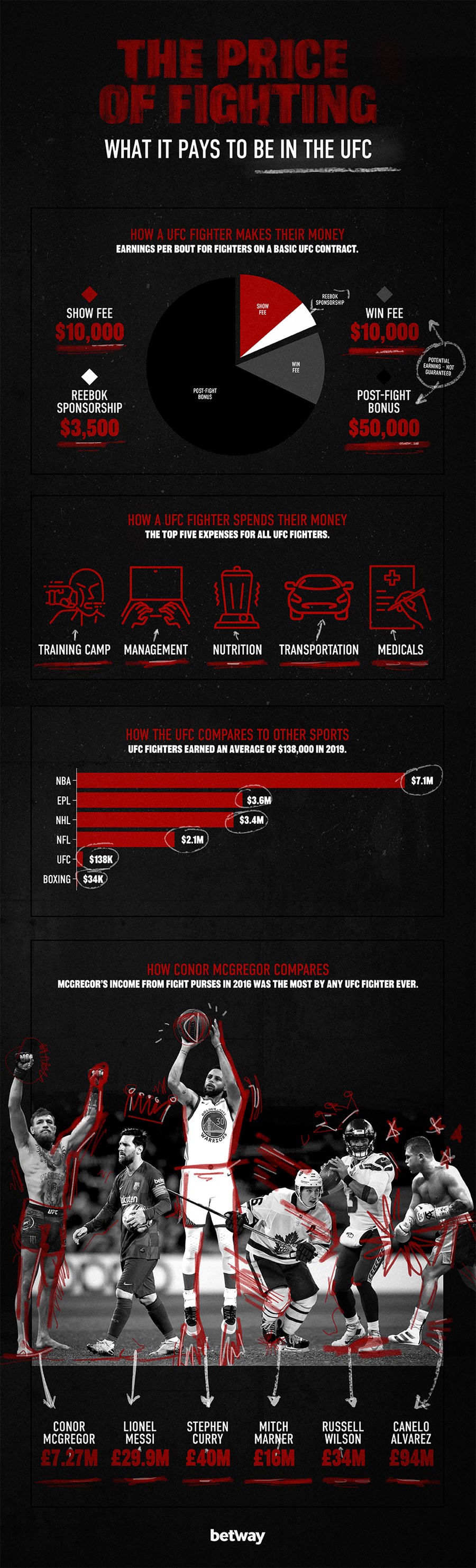

Despite UFC annual revenue approaching $1bn in 2019, many of its fighters are left living pay cheque to pay cheque.

You may think that getting professionally punched in the face and choked unconscious for other people’s entertainment pays well.

After all, Conor McGregor made $47m in 2018 despite entering the octagon just once that year.

His opponent in that fight, Khabib Nurmagomedov – who is in the UFC betting to repeat his win over McGregor in any potential rematch – earned $11.5m across the same period.

The reality is, however, very different.

Fighters at the start of their UFC careers sign a contract which pays $10,000 to fight and $10,000 to win.

That may sound like a decent amount of money for one night’s work, but the costs of being a professional fighter mean they actually take home very little.

“Fighters probably spend the best part of $4,000 on their camp, and they usually pay their manager 10 per cent of their purse – sometimes more,” says Jim Edwards, a renowned MMA journalist who has covered the sport for a variety of publications since 2014.

“By that point they're already $5,000 down. You then have to think about food and nutrition – a few hundred here and there – which adds up over the course of their camp.

“If you're on the bottom rung, the UFC only pay for the travel costs of one cornerman, so then you’ve got to fly in another cornerman. Even if you were staying in London, look at the hotel prices – it’s probably the best part of $1000 for a few nights at a decent hotel.

“By the time you take tax out of that as well, you’re left with what? A few grand? Maybe even a few hundred dollars if you lose.

“A lot of these guys basically live fight to fight, barely making any money.”

The earning power of UFC fighters has been affected in recent years by the Reebok outfitting deal, which requires them all to wear a Reebok fight uniform.

Fighters were previously free to agree deals with sponsors to wear their apparel and display logos on fight attire, allowing them to increase their earnings by a significant amount.

They still receive payment as part of the Reebok deal – $3,500 a fight for someone on a basic contract, up to $40,000 a fight for champions – but the vast majority of fighters have seen their earning potential take a real hit.

“Before that deal came in, there was quite a lucrative sponsorship market within MMA. There was a lot of sponsorship money going around, people were endorsing fighters left, right and centre,” says Edwards.

“Now, it's pretty safe to say that it's only that upper echelon of fighters that are getting paid sponsorship.

“There used to be people making more money through sponsorship than they were from their actual fight purses – Reebok destroyed that.”

For many fighters, particularly those who have just signed to the UFC, their lack of financial security means they have to balance their MMA careers with other work.

“The reality of the situation is that most of these guys, especially before you get to the UFC, will have another job,” says Edwards.

“A good example is Jai Herbert, who literally just signed to the UFC. He was Cage Warriors champion – the cream of the crop in Europe – and only just quit his job as a bricklayer once he got a UFC contract.

“Another is Jack Marshman, who was in the Army for a heck of a long time. He only gave up his Army duties in July 2019, after six fights in the UFC.”

To understand why these athletes, who are at the very top of a very lucrative sport – UFC revenue nearly touched $1bn in 2019 – still struggle financially, you must look at the structure of the industry.

Unlike boxing, in which fighters are protected by the Ali Act – a piece of legislation passed in 2000 which checks the power of promoters – mixed martial arts is totally dictated by its governing bodies, in this case the UFC.

“It's not like boxing, there's no Ali Act between fighter and promoter,” says Edwards. “The promoters hold the cards, that's just the situation in MMA.”

Consequently, fighters who are yet to make a name for themselves – or, in other words, those who are yet to make serious money for the UFC – hold very little power in contract negotiations.

A potential solution is a fighters’ trade union – such organisations have given athletes in the NBA, NFL, MLB and NHL the power to negotiate collective agreements with owners.

The prospect of a fighters’ union has been debated for several years, but so far, the obstacles have proved too big.

Such an organisation would need the backing of big names, those fighters who hold sway with the UFC thanks to their pay-per-view draw.

“The most influential fighters are the best paid, so it's not in their interests to do it. In their mind, they don't want to bite the hand that feeds them,” says Edwards.

Such unwillingness among top-level fighters leaves those lower down the rankings at the whim of the UFC.

“Essentially, they have no power. If someone spoke out now against the UFC, they would be cut.”

Despite all this, fighters continue to line up in droves for their chance in the UFC, with the sport of mixed martial arts stronger now than it ever has been.

“You do it because you love the sport,” says Edwards. “There is a certain buzz with MMA - it's not like anything else.

“MMA is just a batshit crazy sport and these fighters know there is nothing like it. That's why it gets away with not being the best paid.”

In the end, though, that obsession with the sport and with professional competition can only go so far.

“Money matters to fighters just as much as the rest of us, but the balance of power in the sport means that they just don’t hold the cards.

“Everyone wants to provide for their family at the end of the day. Look at Conor McGregor – look how much money he's made, yet he's still obsessed with making more.”

Visit Betway's UFC betting page.